What the Gut Microbiome Can Tell Us About Concussions

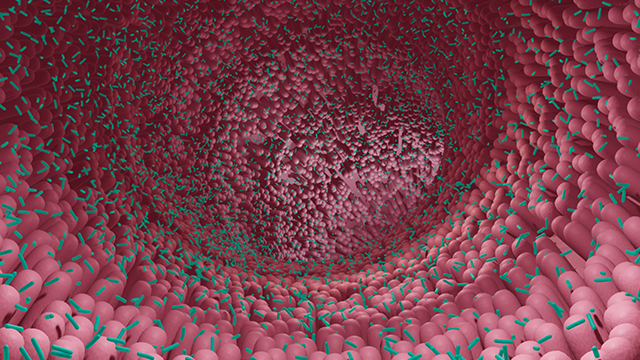

April 26, 2023 - Eden McCleskeyConcussions can cause serious damage to the brain and body, but they are notoriously difficult to diagnose. A new study by Houston Methodist researchers suggests that signs of a concussion can be found in a surprising location: the gut microbiome.

The study, conducted with Division I college football players over the course of one season, found a post-concussion drop-off of two bacterial species normally found in abundance in stool samples of healthy individuals. It also found a correlation between traumatic brain injury linked proteins in the blood and one brain injury-linked bacterial species in the stool.

"Now, potentially, we can say, 'OK, we don't see anything on the neuroimaging, we don't see anything in the blood test, but we found you do have a deficit of this bacteria, which is very important for the immune system recovery, so you should rest until that gets better,' " says Dr. Sonia Villapol, a Houston Methodist neuroscientist who led the study in collaboration with the Rice University Department of Athletics and Information Science.

The researchers believe the study findings demonstrate that a simple diagnostic test can be developed to track the impact of concussions and signal when it is safe to return to action, giving new meaning to the phrase "trust your gut."

Such a test would be a big advance because there's currently no definitive, objective diagnostic test for concussions. Brain movement within the skull may cause injury to nerve cells, but it doesn't typically cause skull fracture, brain bleeding or swelling, and microscopic cellular injuries are not visible on imaging tests like X-rays, CT scans and MRIs. As a result, the most commonly used test for the diagnosis of concussions relies exclusively on self-reported symptoms like blurry vision, dizziness, nausea and headaches.

"Because asymptomatic individuals can still have mild brain injuries that impact their short-term and long-term cognitive health, indicative biomarkers corroborating a brain injury diagnosis are needed," says Dr. Gavin Britz, director of the Houston Methodist Neurological Institute and co-author of the study. "This research demonstrates the vast diagnostic potential of studying the gut microbiome as a reflection of subtle changes in the central nervous system."

An article on the Houston Methodist-Rice study recently was published in Brain, Behavior & Immunity – Health.

To examine the diagnostic potential of the gut, the researchers looked at blood, stool and saliva samples from 33 players, four of whom were diagnosed with major concussions. Additional layers of testing were conducted on those who'd suffered the concussions.

The concussed players' gut bacteria decline, which was steep, was found in the species Eubacterium rectale and Anaerostipes hadrus. Additionally, among players exposed to subconcussive impacts, a correlation was noted between traumatic brain injury linked proteins (S100β and SAA) in the blood and the Eubacterium rectale species in the stool.

The brain-gut connection

Dr. Villapol's lab currently is focused almost exclusively on analysis of the gut microbiome, which may seem like unusual territory for a neuroscientist until you realize what she is looking for.

Her portfolio includes studies looking at the microbiome in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, analyzing microbiome changes in hemorrhagic stroke patients to predict future strokes, looking for predictors of long COVID in the gut microbiome and a collaboration with Baylor College of Medicine to design probiotic therapies in animal models of severe accidents.

"There is a link between the microbiota in the gut and the brain's response to trauma or even neurodegenerative disease," Dr. Villapol says.

After a concussion or accident, often the first thing that happens, within milliseconds, is vomiting. This occurs courtesy of the vagal nerve directly connecting the brain to the stomach.

The second connection is systemic. Injuries cause inflammation, sending cytokines and metabolites circulating through the blood, resulting in inflammation throughout the body. This causes changes in the gut, with certain bacteria all but evaporating within hours to days.

The third and slowest connection is metabolic.

"Dysbiosis occurs when the good bacteria doesn't return and thus doesn't produce the anti-inflammatory antioxidants to help the body get over the trauma, and bad bacteria begins to accumulate, releasing toxins and increasing inflammation, which then circulates back through the blood and brain again," explains Dr. Villapol. "The connection is bidirectional, so you can get trapped in a bad feedback loop that is difficult to break out of."

From an evolutionary point of view, stomachs are very important to survival and sensitive to danger. They can be both the first and last organ to register an issue.

"Until your gut microbiome has returned to normal, you haven't recovered," says Dr. Villapol. "This is why studying the gut is so useful. It doesn't lie. And that is why there is so much interest in using it for diagnostic purposes."

Addressing the diagnostic gap

Gut microbiome analysis represents a corrective to the vague and subjective nature of cognitive effect testing, which is undermined by athletes frequently underreporting symptoms. It is estimated that only one in nine symptom-provoking concussions are reported, leaving the other eight vulnerable to further injury or unchecked inflammation.

Recognizing that it is necessary to develop a more reliable test, researchers have identified dozens of brain injury biomarkers, though it has so far proved difficult to develop a commercial blood test that is sensitive enough to detect these tiny increases in protein concentrations.

Testing the stool samples of players recently concussed, however, is easy and accessible nationwide.

Next steps

Because the study only included four players diagnosed with major concussions, the results will need to be confirmed in a larger sample size.

Dr. Villapol is hoping to conduct a similar study soon using women's soccer athletes.

"Women and men don't have the same immunities or gut microbiomes, and as a woman and a mother of daughters, I would hate to be that researcher who only looks at men's issues while overlooking women," Dr. Villapol says. "Women's soccer players have very high rates of concussions, as well, and all the same problems when it comes to existing diagnostic methods."

In the future, Dr. Villapol also plans to research the potential probiotic or prebiotic treatments to help improve recovery from concussions and stave off the long-term neurological damage associated with them.