Can tDCS Improve Motor Recovery After Stroke?

April 4, 2022 - Todd AckermanMild electrical stimulation of the brain is safe and feasible in the early days after a stroke, according to a clinical trial led by a Houston Methodist investigator.

The trial, results from which were unveiled April 4 at the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2022 meeting, represents one of the first attempts to use transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in the understudied but crucial early phase after a stroke, when the speed of recovery is typically fastest.

"We want to find out if there are advantages to intervening with tDCS when there's more going on neurophysiologically with the patient," says Dr. Timea Hodics, a Houston Methodist neurologist and the study's first author. "Can tDCS be more effective when it's applied in this early phase, where a lot of the plastic changes actually are occurring?"

Previous tDCS research with stroke has focused on the technology's use in the period after the patient has plateaued and symptoms have become chronic. There has been increased interest more recently in the early time window, however.

The particular benefits of tDCS

Dr. Hodics, who presented the new trial findings at AAN, praises the technology because it is noninvasive, inexpensive, portable and easy to set up and use.

The trial, which looked at the motor recovery of the upper extremity, was not large enough to conclude whether transcranial direct current stimulation improves such function. Participants who got the real treatment improved significantly after treatment, but so did those getting sham therapy.

Improving stroke recovery beyond what is achievable with standard rehabilitative treatment (SRT) alone would be a major advance. The fifth cause of death in the U.S., stroke is also a leading cause of serious long-term disability, primarily paralysis and motor control difficulties. It reduces mobility in more than half of stroke survivors 65 and older.

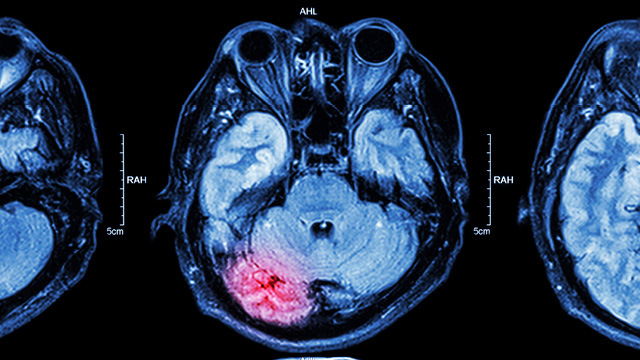

Stroke events occur when a blood vessel that carries oxygen and nutrients to the brain is either blocked by a clot or bursts. The resulting poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death.

An explosion of research interest

Neurological research with tDCS has been around for decades, but captured greater interest in the 1990s and 2000s following the publication of some promising studies by European researchers. It is currently exploding, according to Dr. Hodics, a reflection of its "extremely promising and noninvasive nature."

All told, according to clinicaltrials.gov, some 1,400 registered clinical trials currently are investigating transcranial direct current stimulation's possible therapeutic benefits into everything from Parkinson's to brain trauma to depression. About 300 of them concern stroke.

One small 2010 study found tDCS improved the motor skills of stroke patients threefold compared to those who received a placebo form of stimulation and the same amount of physical and occupational therapy.

Despite its promise, the FDA has not yet approved tDCS for any use.

A benign form of intervention

The technology uses low direct current delivered through electrodes on the head. It works by exciting or inhibiting the brain's neurons in the stimulated area.

If it's felt at all, the current causes the patient no more than tingling or slight itching.

Dr. Hodics' single-center, triple-blinded study enrolled 36 participants who suffered an ischemic stroke in the previous five to 15 days and who were experiencing arm weakness. Randomized into one of two study arms — standardized rehabilitation therapy (SRT) plus tDCS or SRT plus sham stimulation — the participants received 20 minutes of stimulation at the beginning of each one-hour-long arm exercise treatment for 10 sessions over two weeks. Participants were recruited from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Early intervention safe but benefit unclear

Outcome measures were collected at discharge, three months and 12 months.

No safety concerns were identified in the participants.

Subjects in both groups showed significant improvement over time. Dr. Hodics says that could be due to the general tendency of stroke victims to improve with time, a learning or training effect, or a placebo effect.

Next up: larger, more individualized trial

Dr. Hodics downplays the failure of tDCS to outperform sham therapy, noting that because of individual variability, researchers would have needed about 300 subjects to find the suspected degree of difference between the two groups. She emphasizes that the pilot study was conducted to help design a larger follow-up study and "achieved just that."

Next up for Dr. Hodics is such a larger follow-up study, complete with a protocol individualized for participants. She is in the process of designing that study now.

"I think at this point, the most informative thing is to understand better what makes the intervention successful in a particular patient," says Dr. Hodics. "But there's no understating the potential of such a benign form of intervention in patients who badly need something besides standard rehabilitative treatment."

Study collaborators included researchers at University of Texas Southwestern, MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital in Washington, Georgetown University and the NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.