Getting people vaccinated remains the top COVID-19 priority, but a Houston Methodist doctor notes that monoclonal antibodies are also a valuable tool against the pandemic's spread.

Dr. Howard J. Huang, a Houston Methodist pulmonologist, said the immune-boosting drugs are highly effectively at preventing hospitalization in high-risk patients as long as they are given promptly. The drugs, once in short supply, are now very accessible.

"Monoclonal antibodies are a good option for high-risk people who are unvaccinated or are vaccinated but didn't produce a strong response," says Dr. Huang, chief of lung transplantation at Houston Methodist. "They give their immune system a leg up until they can mount their own response."

Monoclonal antibody therapy came to the public's attention last fall when President Donald Trump received it after contracting the virus. The treatment was credited for his quick recovery.

Earlier this month, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) extended monoclonal antibodies' potential application, authorizing its use as a preventive in those at risk because they were exposed to the virus. The authorization was based on the results of a large clinical trial that found the antibodies prevented symptoms in household contacts of people who recently tested positive.

This action marked the first time a coronavirus antibody treatment has been approved for use as a preventive. In a statement, the FDA emphasized that the authorization didn't mean monoclonal antibodies should be considered a vaccination substitute.

Monoclonal antibody use picking up again in the last month

Dr. Huang and his Houston Methodist colleagues have treated more than 6,000 patients with monoclonal antibodies — the numbers piling up initially during the winter, now surging again the last month. Most of the treatment has been provided at the hospital's outpatient clinics.

In an effort to increase access to the therapy, Houston Methodist also partnered with urgent care clinics around the city. Use of the drugs was limited because it had to be administered through an IV infusion, but the expanded authorization means the drug can be given as a subcutaneous injection for post-exposure prophylaxis. However, IV infusion is still the delivery route for high-risk patients who test positive.

The recommendation is to give monoclonal antibody treatment within 10 days of the onset of symptoms, but Dr. Huang emphasizes, "the sooner, the better."

"Time is of the essence," says Dr. Huang. "If you're going to make a difference with this therapy, you have to give it early to block replication of the virus. If the virus has had a lot of time to replicate, at some point it doesn't matter if you give the antibodies."

To expedite treatment, Houston Methodist instituted a program in which pharmacists call patients immediately after a test confirms they've contracted the virus to educate them about the drugs' potential benefits.

Patients with diabetes, high blood pressure, heart or lung disease, or a compromised immune system are typically strong candidates, says Dr. Huang. Such patients are at high risk for COVID-19's progression to severe disease, hospitalization and death.

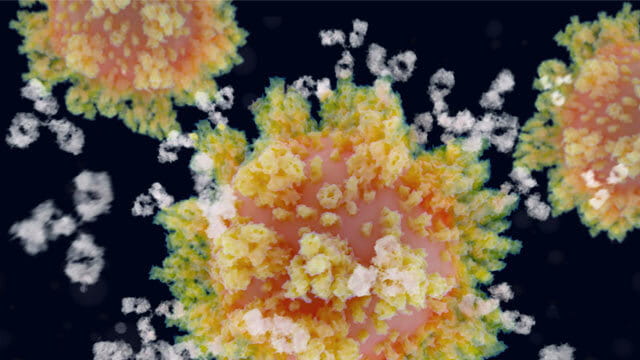

Monoclonal antibodies protect against severe illness by overwhelming the virus before it reaches the lungs, while it's still mostly in the nose and throat.

Monocolonal antibody treatment delivers a dose of antibodies designed for optimal potency

They work on the same principle as convalescent plasma, the century-old therapy in which patients are given the blood product of people who have recovered from the disease. Convalescent plasma therapy in COVID-19 has shown variable efficacy because people infected make vastly different levels of antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies, which originate in recovered patients but are synthetically designed for optimal potency, deliver a consistent dose.

The treatment is free under a federal program. In the spring, the Biden administration announced a $15 million plan to improve access, particularly among vulnerable populations.

The FDA-approved monoclonal antibodies are the cocktail of casirivimab and imdevimab, developed by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and sotrovimab, developed by Vir Biotechnology and GlaxosmithKline. Distribution of a third antibody therapy, Eli Lilly's bamlanivimab and etesevimab cocktail, was halted earlier this summer because it has not shown to be effective against new variants of the virus.

Dr. Huang emphasizes that the two approved antibodies constitute a useful weapon in doctors' arsenal — often the difference between infected patients not developing COVID-19 or getting over it quickly and those ending up in a hospital.

"The community needs to step up and get vaccinated to break the virus' chain of transmission," says Dr. Huang. "But until they do, monoclonal antibodies are a useful tool for people with weak immune systems."